This essay examines the exploitation film I Spit on Your Grave (1978) and its recent remake (2010), and how both these films make strong comments about the culture which they were released in and the context which they were interpreted. The original film was visually enhanced and re-released on Blu-Ray this year, and therefore, along with its remake stands as a contemporary text. The essay focuses on the cultural significance of the previously banned movie being remade for a modern audience, and the voyeuristic aspects of both films. The way the film represents meaning to the audience through sound and image will also be discussed, representation being defined as the ‘process by which meaning is produced and exchanged between members of a culture… [involving] the use of language… signs and images which stand for or represent things’ (1997, p. 15). The aim of this essay is to shed light on the social and cultural significance of horror films, which are braver in their exploration of society’s taboos, and the reasons why society needs these films, as evidenced by the recent trend of their remakes. The essay also aims to explore the feminist qualities I Spit on Your Grave contain, for the purpose of this essay feminism can be defined as ‘the advocacy of equality for the sexes, in opposition to patriarchy and sexism’ (Macionis & Plummer, 2008, p. 883).

In the last decade swarms of horror films have risen from the ground in the form of remakes, these include:

(2003), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

(2005), The Amityville Horror

(2006), The Hills Have Eyes

(2007), Halloween

(2009), Friday the 13th

(2009), The Last House on the Left, and most recently

(2010), I Spit on Your Grave

Lizardi (2010, p.114-115) offers two suggestions as to why these films are being remade, one is that remakes are ‘commercial products that repeat successful formulas in order to minimize risk and secure profits in the market place’, while the other reason is that horror remakes have the potential ‘to reveal something to us about our recurrent fears, anxieties and hopes for the future’. Becker (2006, p. 47) contends with this view by suggesting that horror films represent ‘society’s collective nightmare’, which contain repressed issues that must be confronted and resolved. It is worth noting that the original versions of these horror remakes mostly stem from the period of slasher films made in the 1970s, an era which was known for the carefree hippie generation and the contrasting bloodshed of the Vietnam War. Considering that ‘films are best understood in relation to the periods in which they were produced and consumed’ (Lizardi, 2010, p. 115), it is necessary for me to explore the culture that the original slasher films were unleashed upon, culture being defined simply as ‘the beliefs, values, behaviour and material objects that constitute a people’s way of life’ (Macionis & Plummer 2008, p. 882).

With the hippie revolution dissipating, and the war in Vietnam alive and well, the American culture was slowly descending towards ‘the sinister, the heavy, and the darkly forbidden’ (Becker, 2006, p. 48). During these times, the catchy pop songs of the early 60s had been cancelled out by the dark sounds of The Doors and Led Zeppelin, while the film industry turned to horror with films like Night of the Living Dead (1968) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974). These films revealed ‘a shift in the worldview of the hippie counterculture, which had its considerable hopes in the possibility of significant progressive social change undercut by immense social traumas of the late 1960s and early 1970s’ (Becker, 2006, p. 43).

In the opening scene of Wes Craven’s infamous Last House On The Left (1972) one of the two female protagonists – before leaving to a Bloodlust concert – is given a necklace by her father, the camera zooms in as she puts it around her neck, revealing a silver peace symbol, a cultural icon of the hippie movement. The camera holds onto this image before fading into a fixed shot of a forest, showing the two girls frolicking towards the camera, serene music playing softly in the background. This scene is later juxtaposed when the two girls are kidnapped; the terror on the girls’ faces are shown in extreme close ups during the scenes of their rape and torture. The progression of violence is eventually capped off by showing a close up of the intestines of one of the girls being pulled out of her body; throughout all these scenes the camera is static and the music is dark and synthesized. This strong contrasting imagery represented the death of the hippie movement, and is a consistent motif of the horror films of the 70s. It was the filmmakers way of getting to the ‘guts’ of their films message, which was ‘there is a war going on, and blood is being spilled.’ A reality that was swept under the rug in the ignorant bliss of the 60s hippie counterculture.

Last House on the Left, along with I Spit on Your Grave were banned in more countries than they were allowed, yet despite this they have both been recently remade. Wes Craven says of his film’s remake “I think it is a film for its times… it’s been a very chaotic eight years. Eight years of… warfare and reactions to 9/11… 9/11 perhaps was the ultimate home invasion… [It was] profoundly shocking to the American psyche. So I think that there is certainly a profound relevance to this film [in modern times]” (Lee, 2009, p. 1). Considering the original films were a direct response to the atrocities of the culture at the time, are these remakes also a response to the terrors of today’s society? Film scholar Stephen Prince suggests that ultra-violence in horror movies are used ‘to comment on the social violence of the era’ and therefore the films can be seen ‘as a form of social commentary’ (Becker, 2006, p. 56), while Sharrett (2009, p. 33) believes that these remakes are ‘a response to the atrocity that was the Bush era’.

The original I Spit on Your Grave and its remake follow a simple three part narrative structure, known as the rape and revenge structure. Act I shows the female protagonist being raped by a group of men, Act II shows her recuperation, and Act III involves the female protagonist exacting violent revenge on each of her attackers. The biggest difference between the original film and its remake is the original focuses more on the total depravity of the rape scenes, while the remake instead focuses on the violent revenge. It seems that the anxieties of 9/11 and the war in Iraq, along with the ‘atrocities cued from Abu Ghraib and the Bush-era practice of… enhanced interrogation techniques’ has mirrored itself into the depiction of violence in today’s horror movies (Hamid, Lucia & Porton, 2009, p. 2). The hugely popular Saw (2004-present) and Hostel (2005-present) films have spawned a new sub-genre of horror called ‘torture porn’, which stems from their depiction of extremely graphic torture methods. I Spit on Your Grave’s (2010) revenge sequence employs the popular torture style of the Saw and Hostel films, with the female protagonist, Jennifer Hill, creating elaborate traps and torture devices to make the rapists suffer for their actions. One scene shows Jennifer taping one of the rapists to a tree, forcing his eyes open with fish hooks, pouring fish guts on his face and then leaving him there for the crows to peck his eyes. Another scene has Jennifer pulling one of her attackers’ teeth out with pliers; none of this occurs off screen.

Sharrett (2009, p. 32) states that the increasing budgets for these horror remakes allow the filmmakers ‘to pursue more extravagant ways of destroying the human body’ and that this glorification of violence and torture is a ‘symptom of the state of culture’ (Sharrett, 2009, p. 37). In the documentary on US torture methods, Taxi to the Dark Side (2007), George Bush makes the comment ‘one by one the terrorists are learning the value of American justice” (Gibney, 2007), this parallels the justice that the lead actress in I Spit on Your Grave enacts on her attackers, is this remake’s use of torture as justice a social comment on the torture tactics used by US soldiers to avenge the 9/11 attacks? Becker (2006, p. 48) asserts that due to the ‘1968 police brutality at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, the inexorable bloodshed of the war in Vietnam, and the 1970 killings of students by the National Guard at Kent State, the government seemed to consider violence not only an acceptable but a desirable solution’, it is arguable that the same message is being made in modern times with the Iraq War, and therefore the remakes of the Vietnam era films are attempting to make a similar social commentary on the nature of violence. The question begs to be asked, is this social commentary necessary? Does it contribute to or glorify violence? Barrett’s (2006, p. 115) answer to this question is that ‘in reducing violence to nothing more than visual pop culture fodder… the very violence that is under the justification of the war on terror… becomes all the more acceptable’, this suggests that in watching these films, we as an audience are becoming desensitised to the very real violence that occurs off screen.

I Spit on Your Grave is ‘acclaimed or reviled, depending on your point of view, as the most powerful or repulsive rape revenge melodrama ever filmed’ Crowdus (2003, p. 32). It is indeed a film which has received both scathing criticism and passionate defence, depending on the context it is viewed in, context being the ‘time, place or mindset in which we consume media products’ (Williams, 2002, p. 1). Film critic Joe Bob Briggs believes that the film was ‘destroyed by critics, in particular by Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel’ (Crowdus, 2003, p. 32), Ebert called the film ‘an expression of the most diseased and perverted darker human natures’ while Siskel suggested the movie would encourage people to commit rape (Crowdus, 2003, p. 32).

Ebert criticised I Spit on Your Grave as ‘a film without a shred of artistic distinction’ (Ebert, 1980, p. 1) because of the context in which he viewed it; he watched it under the impression that it was supposed to be a sleazy exploitation movie, and he viewed it in a theatre full of what he believed to be ‘vicarious sex criminals’ (Ebert, 1980, p. 1). The bulk of his review focuses on the audience, and this colours his judgement of the film; he states that ‘as a critic, I have never condemned the use of violence in films if I felt the filmmakers had an artistic reason for employing it. “I Spit on Your Grave” does not.’ (Ebert, 1980, p. 1). Ebert reviewed a similar rape and revenge film much later on in his career titled Irreversible (2002); both films share in common extended sequences of brutal and unflinching rape, however, Ebert applauds Irreversible’s artistic merit due to its reverse chronological structure ‘which makes Irreversible a film that structurally argues against rape and violence’ (Ebert, 2003, p. 1). Lacey (2009, p. 30) suggests that ‘there can be no certainty that the individuals in the audience will read the text in the way it is intended’; which as you are about to discover, is the case with Ebert’s review.

Exactly what message was the filmmaker trying to make you may be wondering? ‘The director honestly thought he was making a feminist film, and an anti-rape film’ (Crowdus, 2003, p. 33), and he initially released it under the title ‘Day of the Woman’, until it was picked up by distributer Jerry Gross, who changed the title to ‘I Spit on Your Grave’ to increase sales. The director, Meir Zarchi states that ‘when they announced the title I Spit on Your Grave, I hated it and I still do’ (Fidler, 2009, p. 40). Zarchi explains in his commentary for the DVD that the film was born from a personal encounter with a rape victim in New York City in October 1974, who he described as ‘a young woman, around eighteen or nineteen, totally naked, a walking corpse covered in mud and blood. She was still in shock and struggled to talk through her broken jaw’ (Fidler, 2009, p. 50). Zarchi took her to the police station to report the crime, but received no help from the uninterested police officer; interestingly the remake includes a police officer as one of the rapists.

As a result of this experience, the female victim in the movie cleans her own wounds after her repeated attacks, and then ‘embarks on a quest of vigilante vengeance, what Zarchi might have seen as the only solution to such injustice’ (Karminski, 2010, p. 6). In light of this context, the film can be seen as a misunderstood text, considering it was initially made to represent the reality and horror of rape and to make a bold feminist statement, as evidenced by the strength of the female character and her justice against her attackers in the final act of the movie. Despite this, the film has been heavily criticised for the enormous length of the rape scenes in the movie; however, Briggs asserts that this is due to exploitation cinema being more honest, direct and confrontational than mainstream cinema, which explains why the film presented the brutality of rape in its raw and unedited form. Briggs suggests that ‘Hollywood doesn’t have a problem with murder but they do have a problem with rape,’ (Fidler, 2009, p. 50) which is clearly evident in the remake’s shying away from the savageness of the rape act, and the intensifying of the ultraviolent revenge scenes. Dawson (2002, p. 1) asserts that the remake did this in good reason as ‘film and media don’t merely report on social reality but actively help to produce it. Thus films such as [I Spit on Your Grave] contribute towards the reproduction of a cultural milieu in which the reality of rape becomes conceivable’.

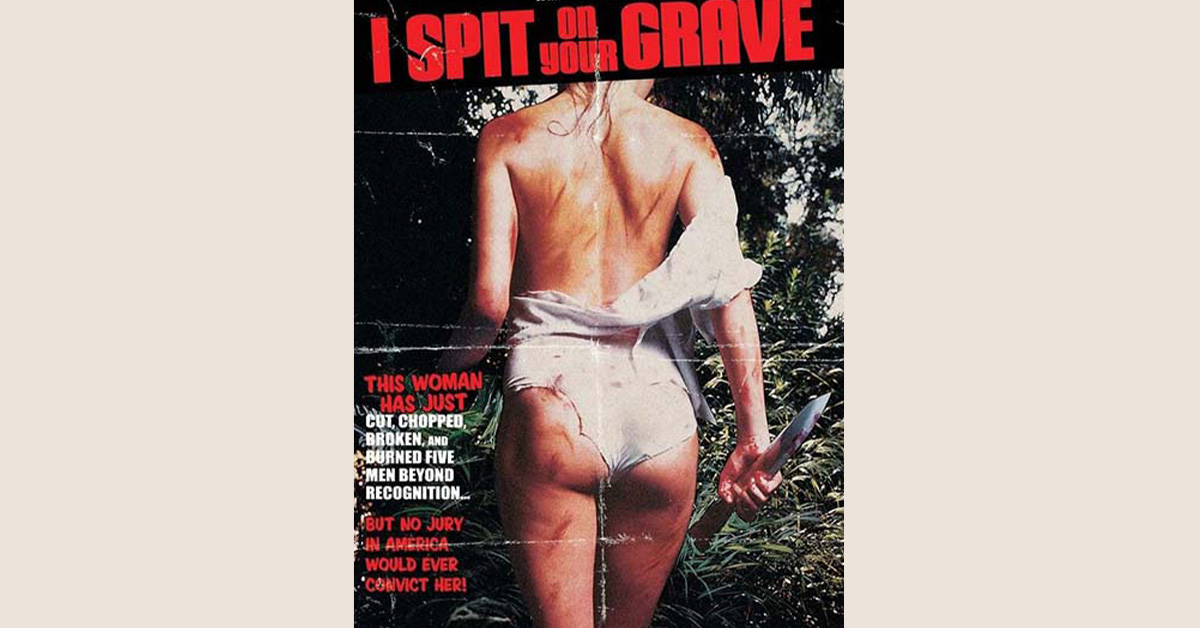

I will be using Mulvey’s (2009, p. 309) interpretation of ‘voyeurism’ as ‘the gaze of the spectator and that of the male characters in the film’, Mulvey (2009, p. 314) further breaks down this voyeuristic gaze into three parts, the camera, the audience, and the characters in the film, which I will examine in I Spit on Your Grave. The two above images of the men leering at the female protagonist in the film are examples of the ‘male gaze’, which is ‘the voyeuristic way men look at women’ (Merskin, 2006, p. 203). The image on the right is from the original, and utilises a low camera angle to represent the power of his masculinity and the submission of the woman, as the man is seen to be looking down and sneering at her while she is forced to look up at him. However, the camera angle cannot be defined as identifying with the male, as the entire film is shot from the perspective of the woman, and not her attackers. Hence why the camera angle shows what the woman is seeing, and not the male. Because of the original’s lack of a ‘male gaze’, the remake included one of the attackers filming the rape scenes with a video camera. In doing this, the screen occasionally shifts from the woman’s point of view, which is what the main cameras are filming, to the point of view of the attackers, which is what the handheld camera is filming. This adds an element of voyeurism which was missing in the first film. Towards the end of the remake, Jennifer turns the camera back onto her attackers and films them being tortured, therefore redirecting the male gaze back at them. The image at the top, from the original, depicts the woman confronting this male gaze in a powerful way.

Apart from the inclusion of the hand held camera in the remake, both films identify only with the female victim. The camera favours her point of view throughout, and in the original the camera never leaves her, staying with her even after her brutal rape to watch her recovery, rather than shifting to see what the ‘bad guys’ are doing. The audience also doesn’t identify with the attackers, and cannot gaze at the woman voyeuristically as ‘there is nothing remotely sexual or titillating about the film, which emphasizes the brutality of the rape scenes’ (Crowdus, 2003, p. 32). The original film also had little dialogue and absolutely no music score except for the sound of the environment and its actors; it was portrayed as a very real depiction of rape in an almost documentary like style, all shown in one take. Both films dedicate the first 20 minutes to identifying the female character Jennifer Hill as ‘an independent woman, a professional woman, an artist who goes her own way’ (Crowdus, 2003, p. 33). There is a scene in the film where Jennifer, upon arriving at her cabin, takes her clothes off and skinny dips into the water. Joe Briggs argues that ‘if Meir Zarchi was making a sleaze film, told from the point of view of the leering male gaze, which is what he’s been accused of, what would he do here?

He would show every bead of water on her breasts and have her do the backstroke. Instead what does he do? The longest of all long shots in the history of all long shots’ (Fidler, 2009, p. 47), in this scene, the camera doesn’t zoom in on Jennifer’s naked body, but instead veers off into the distance, perhaps to represent that somebody is watching her – the ‘male gaze’ – however, the camera and the audience are completely detached from the point of view of the criminals and are therefore not allowed their voyeuristic sight. The only obviously voyeuristic elements of both these films are found in the posters, which show the female body from behind, with her clothes ripped to reveal her buttocks. Merskin (2006, p. 209) suggests that in this context the viewer can gaze for as long as he likes, ‘permitted by the photos reassurance that the woman is unaware of his look’. These posters contend with Merskin’s (2006, p. 203) view that ‘female identity in advertising is almost exclusively defined in terms of female sexual identity’, which can be clearly seen in the images portrayal of the female victim as being sexy, even though she has just been brutalised. However, this is only evident in the film’s advertising, as it was marketed this way to increase sales, and considering that ‘sex had become the commodity used by advertisers competing for consumers’ attention’ (Merskin, 2006, p. 203), it is no surprise that this was exploited. In fact, there’s a good chance that the film wouldn’t have been popular enough for a remake if it wasn’t for the original’s provocative front cover, which it is known for. The fact that the remake decided to use an almost exact replica of the original’s poster suggests that ‘the use of sexual imagery in advertising… shows no signs of slowing’ (Merskin, 2006, p. 215).

In conclusion, this exploration of the film I Spit on Your Grave and its remake aims to establish the cultural significance of the films initial release in the 70s along with its predecessor Last House on the Left, and its recent reimagining. It is clear that the film was created with the intention to open the viewer’s eyes to the reality of rape and violence against women, which is an undeniable shadow of human nature that exists and stalks society to this very day. The essay also sheds light on the various interpretations of the film, some of which have been lost in translation due to the context in which the film was advertised. The essay also explores the feminist qualities which the film possesses and how these were represented through the camera angles favouring the female’s point of view. I will end my essay with Joe Briggs opening line of his commentary for I Spit on Your Grave, ‘what we’re going to decide here is, is this the most disgusting movie ever made or is it the most feminist movie ever made?’ (Fidler, 2009, p. 38)

What’s your opinion of the film? Do you believe it has a feminist agenda, or is purely a piece of exploitation? Do you think there is any cultural significance to these films being remade, or is it just a cash cow?

If you liked this post, be sure to subscribe!

References

- Barrett, P., 2006, ‘White Thumbs, Black Bodies: Race, Violence, and Neoliberal Fantasies, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas’ , The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 95-119.

- Becker, M., 2006, ‘A Point of Little Hope: Hippie Horror Films and the Politics of Ambivalence’, The Velvet Light Trap, Vol. 57, pp. 42-59.

- Blastr 2009, Wes Craven on why Last House on the Left is a remake for our times, Blastr, 20 February, viewed 20 May 2011 <http://blastr.com/2009/02/wes-craven-on-why-last-house-on-the-left-is-a-remake-for-our-times.php>

- BluRayMedia 2011, ‘I Spit on Your Grave Remake Video Camera [image] in I Spit on Your Grave (2010) Screenshots, viewed 18 May 2011, < http://bluraymedia.ign.com/bluray/image/article/114/1147866/i-spit-on-your-grave-2010-20110204101524859_640w.jpg>

- Craven, W 1972, Last House on the Left [DVD], Director W Craven, Hallmark Releasing Corp, United States

- Crowdus, G., 2003, ‘Cult Films Commentary Tracks and Censorious Critics an Interview with John Bloom’, Black and White Photographs, Vol. 28, No. 32-34.

- Dawson, L., 2002, ‘No defence for rape scenes’, Europe Intelligence Wire, October 26, 2002.

- Ebert, R., 1980, I Spit on Your Grave Review, viewed 20 May 2011, <http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19800716/REVIEWS/7160301/1023>.

- Ebert, R., 2003, Irreversible Review, viewed 20 May 2011, <http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20030314/REVIEWS/303140303/102>.

- Fidler, T., 2009, ‘Joe Bob Briggs and the Critical Commentary on I Spit on Your Grave’, Colloquy Text Theory Critique, Vol. 18, pp. 38-58.

- Gibney, A 2007, Taxi to the Darkside [DVD], Director A Gibney, THINKFilm, United States.

- Groening, M., 1995, The Simpsons: The Complete Seventh Season [DVD]. 20th Century Fox, United States.

- Hall, S., 1997, ‘The Work of Representation’, Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, Sage, London, pp. 15-64.

- Hamid, R., Lucia, C., & Porton, R., 2009, ‘The Horror of it All’, Cineaste, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp.2.

- Iliadis, D 2009, Last House on the Left [DVD], Director D Iliadis, Rogue Pictures, United States

- Kaminski, M., 2010, ‘Is I SPIT ON YOUR GRAVE Really a Misunderstood Feminist Film?’, viewed 19 May 2011, < http://www.obsessedwithfilm.com/features/is-i-spit-on-your-grave-really-a-misunderstood-feminist-film.php >.

- Lizardi, Ryan., 2010, ‘Re-Imagining’ Hegemony and Misogny in the Contemporary Slasher Remake, The Journal of popular film and television, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 113-121.

- Macionis, J.J. & Plummer, K 2008, ‘Sociology: A Global Introduction’, 4th edition, Prentice-Hall, New York.

- Merskin, D., 2006, ‘Where Are the Clothes? The Pornographic Gaze in Mainstream American Fashion Advertising’, Sex in Consumer Culture: The Erotic Content of Media and Marketing, ed. Reichert, T. & Lambiase, J., Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers, Mahwah, pp. 199-217.

- Monroe, S.R. 2010, I Spit on Your Grave [DVD], Director S.R. Monroe, Anchor Bay Entertainment, United States.

- Mulvey, L., 2009, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Visual and Other Pleasures, 2nd Edition, Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke, pp. 303-315

- ObsessedWithFilm 2010, ‘Day of the Woman’viewed 19 May 2011, <http://www.obsessedwithfilm.com/wp-content/photos/Dayofthewoman.jpg>

- Sharrett, C., 2009, ‘The Problem of Saw: “Torture Porn” and the Conservatism of Contemporary Horror Films, Cineaste, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 32-37.

- Stadler, J. & McWilliam, K., 2009, ‘Screen Narratives: Traditions and Trends’, Screen Media: Analysing Film and Television, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, pp. 155-182

- TipTopTens 2011, ‘I Spit on Your Grave Remake Cover [image] in Top Ten Unrated Movies to Watch, viewed 18 May 2011, < http://www.tiptoptens.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/I-SPIT-on-your-GRAVE-Unrate-Movie.jpg>

- Williams, R., 2002, ‘Media Studies Glossary’, Royton & Crompton School, pp. 1-2.Zarchi, M 1978, I Spit on Your Grave [DVD], Director M Zarchi, Cinemagic Pictures, United States.